Comics Fighting: An Underground War for LGBTQ Visibility

The use of comic style story-telling developed in the late 18th century, starting as satirical cartoon pieces, but slowly evolving into the newspaper staple that they are today. Since their inception, comics have provided a unique way of storytelling that was able to connect with a large variety of audiences. Following World War II, a time also known as the Golden Age of Comics, the medium erupted with larger than life heroes and stories and also reached new and larger than ever audiences.[1] As the comic style developed it continue to attract new diverse communities with an array of characters. Beginning in 1983, comic books and strips started to provide alternative methods of visibility for the LGBTQ+ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, Queer/Questioning, and others) Movement by diversifying the perception of the people in the community, emphasizing political issues that affected the community, and by integrating prevalent social issues into main stream media outlets.

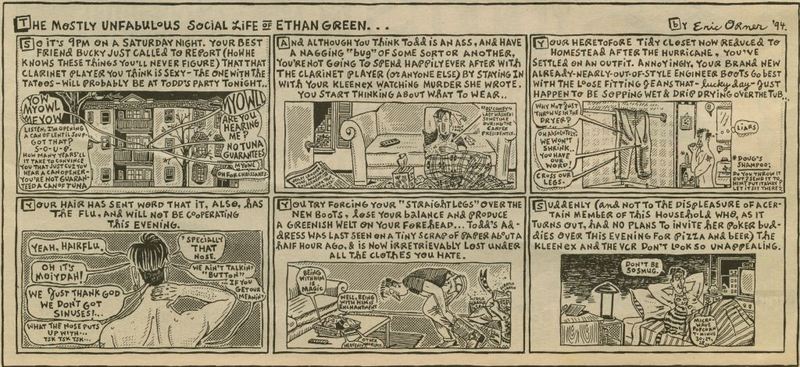

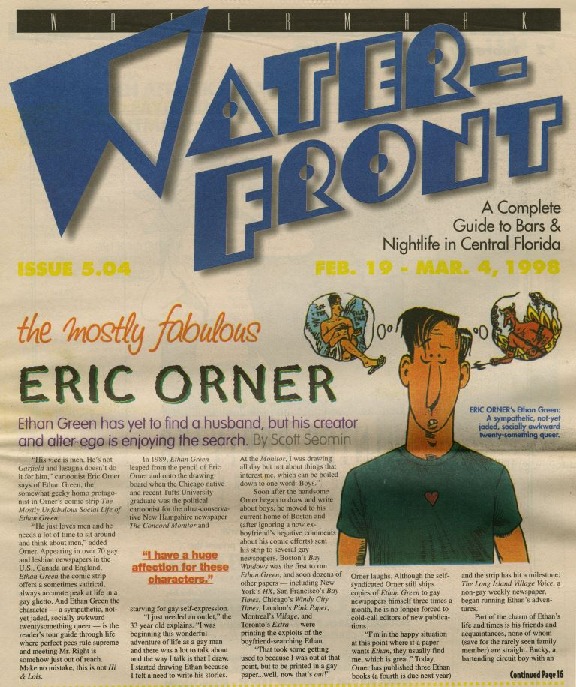

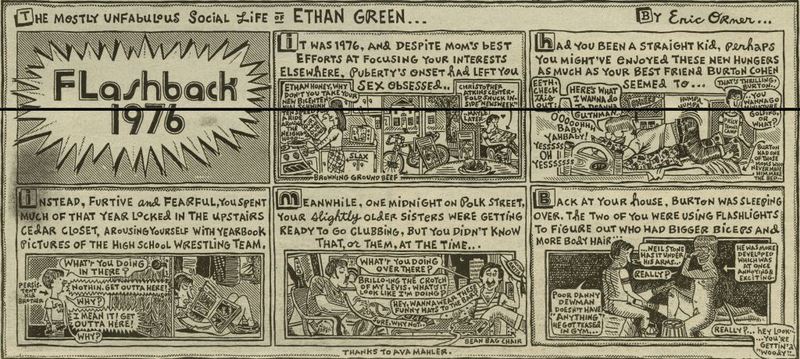

Comic strips such as The Mostly Unfabulous Social Life of Ethan Green sought to demonstrate the journey through life that author Eric Orner experienced.[2] The comic resonated with audiences because it was an accurate portrayal of the evolving gay culture that had been largely missing from more traditional media outlets. In the comic, Orner's title character, Ethan Green, a socially-awkward gay man, maneuvers through life with the aid of his friends, confronting issues of sex, politics, love, and family.[3] The strip became involved in the continuing discussion of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) when Orner had Ethan fall in love with Doug, an HIV-positive (HIV+) character.[4] The story arch addressed the prejudice against HIV+ people even within the LGBTQ+ community.[5] The strip reached even higher notoriety when in 1998, it was established as a permanent piece of The Long Island Village Voice, a non-LGBTQ+ weekly newspaper. This made The Mostly Unfabulous Social Life of Ethan Green the first strictly LGBTQ+ comic strip to transition into traditional media.[6]

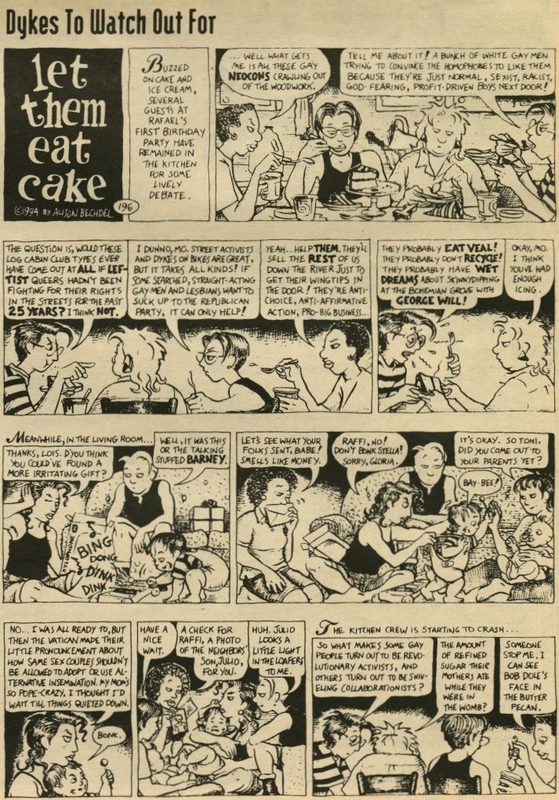

Another comic strip that addressed issues that were directed at the LGBTQ+ community was the lesbian-centric Dykes to Watch Out For by Alison Bechdel. The comic focused on major, and often overlooked, political issues being discussed by a group of friends. Bechdel tackled issues such as prejudice, political competency, and society at large through the comic. A notable example would be in the strip "Lime Light," published in 1994, that addressed the lesbian community’s discrimination against male to female transgendered people.[7] The publication of this strip came almost immediately after the report by the San Francisco Human Rights Commissio, Investigation into Discrimination of Transgendered People, released in September 1994.[8] Bechdel has also addressed the lack of commitment to the LGBTQ+ Rights Movement in the White House, the lack of confident LGBTQ+ leadership, and the downfalls of having a Congress not in line with the president.[9]

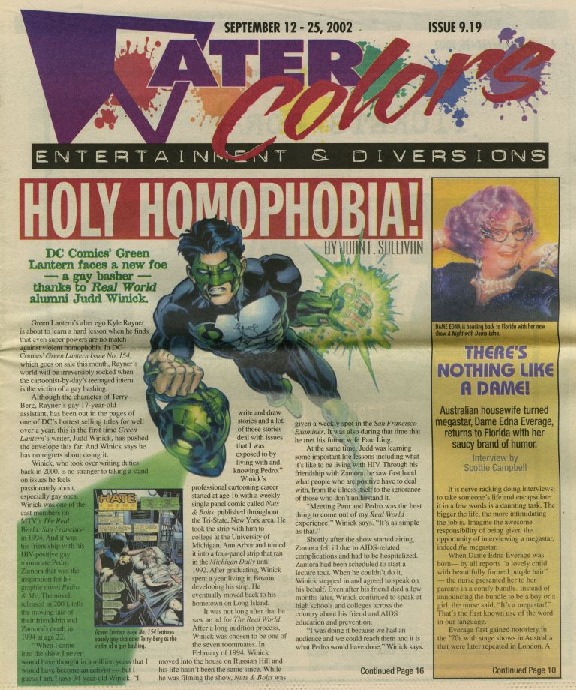

Comic books also made incredible impacts on the development and visibility of the LGBTQ+ movement. Few main stream comic titles attacked the concepts of homophobia head on; however, in 2002, The Green Lantern did just that.[10] In 2000, The Green Lantern writer Judd Winick added Terry Berg, a gay teen, to the cast of regular characters in the comic book. After the character’s involvement for two years, representing the positive sides of coming out and the LGBTQ+ community, the DC Comics writers decided to foreground the social issue of hate crimes in America.[11] The issue addresses that, while characters such as the Green Lantern have huge amounts of cosmic power, those powers have little effect on homophobia.[12] While the hero of the story may not be able to end the conditioning that creates homophobia, the publication of the world's most popular superheroes addressing the issue has contributed to the fight.

Fom 1983 onward, comic books and strips have provided alternative methods of visibility for the LGBTQ+ Movement by diversifying the perception of the people in the community, emphasizing political issues that affected the community, and integrating prevalent social issues into main stream media outlets. This use of comic evolved with the movement that was commonly marginalized in the media into designated tropes. The unique storytelling of comics was able to connect with the LGBTQ+ movement in a way similar to its connection to the American community following World War II. As comics continue to develop, they will continue to attract newer and more diverse communities with their array of characters and stories that represent the people who need to be represented the most.

[1] Kane Anderson, "History of the Superhero Genre," Salem Press Encyclopedia of Literature (January 2016), accessed August 2, 2016, http://eds.b.ebscohost.com/eds/detail/detail?sid=b68e99e4-8966-4f6e-990a-cdd2686d64c9%40sessionmgr107&vid=18&hid=113&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWRzLWxpdmUmc2NvcGU9c2l0ZQ%3d%3d#AN=102165554&db=ers.

[2] Scott Seomin, "The Mostly Fabulous Eric Orner," The Watermark: Waterfront Vol. 5, No. 4 (March 4, 1998): 17.

[3] Ibid. 1.

[4] Eric Orner, "The Mostly Unfabulous Life of Ethan Green…," The Watermark Vol. 1, No. 8 (December 7, 1994): 25.

[5] Seomin, "The Mostly Fabulous Eric Orner," 16.

[6] Ibid. 1.

[7] Alison Bechdel, "Lime Light," Dykes to Watch Out For, The Watermark Vol. 1 No. 6 (November 9, 1994): 18.

[8] Jamison Green, Investigation into Discrimination of Transgendered People (September 1994), accessed August 21, 2016, http://www.hawaii.edu/hivandaids/Tg/Report__Investigation_into_Discrimination_Against_Transgendered_People-ed.pdf.

[9] Alison Bechdel, "From Sublimination to the Ridiculous," Dykes to Watch Out For, The Watermark Vol. 1 No. 7 (November 23, 1994): 16.

[10] John F. Sullivan, "Holy Homophobia!" The Watermark: Watercolors Vol 9, No. 19 (September 25, 2002): 1.

[11] Ibid. 16.

[12] Ibid. 1.