Geanie & Shirley

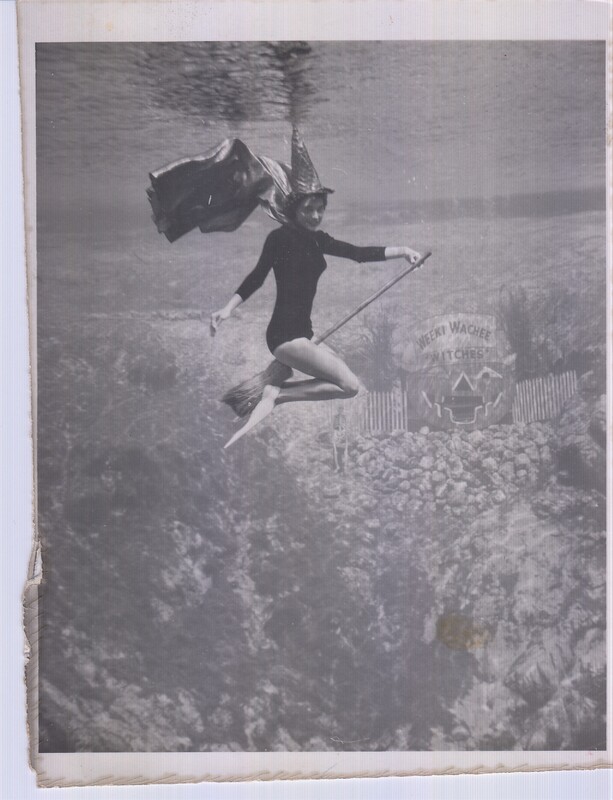

Shirley Herdge came to the Weeki Wachee history harvest with photographs of her mother, Geanie Brooks, who was a mermaid from 1955-1957. In an interview with Shirley, she recalled what she remembered about her mother getting the job: “Mom actually, she was a waitress at Weeki Wachee at the Patio restaurant before she became a mermaid. And of course, they saw her. She is a very beautiful woman. I mean she has movie star good looks. Did very much at that time. She’s tall and statuesque. Long dark hair. And so, they I think invited her to try to be a mermaid. Someone there.” Shirley was eight years old when her mother became a mermaid. As the oldest, she was allowed to occasionally come to work with her mother while her younger siblings were watched by family members or babysitters. Shirley loved having the freedom to roam the attraction: “When mom would be swimming and I would be on the beach or in the water, but nobody bothered me, I was just allowed to kinda’ wander around.” She would walk through the May Museum of the Tropics: “I’d love to see the moths and the butterflies in the display cases.” “Occasionally, I’d go down the river on the Congo Belle, go into the Patio restaurant and they would feed me, and go see mom at the show, or just, kinda’ wander around.”[1]

Geanie left Weeki Wachee in 1957 to sell real estate, but came back for a couple of the mermaid reunions. Her life was filled with interesting jobs. In a typed memoir about her life, Geanie wrote about repairing bulldozers, driving dump trucks, waitressing, managing, bookkeeping, teaching bowling, renovating a historic mill, and so much more. Her illustrious resume began as a teenager, with a position as a welder.

During World War II, there was a high demand for military goods and a labor and construction supply shortage. Especially after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Navy needed more ships. The United States Maritime Commission noted that to supply the ships, 30,000 additional employees were needed just in the shipyards. Thomas M. Woodward, a member of that commission, said “women seem to be the answer, the only one, to the problem” of how to fill all of these jobs with a labor shortage.[2] One shipyard in Tampa, McCloskey shipyard, became specifically essential as they used concrete in place of rolled steel for their ships due to the shortage of steel.[3] 6,000 new jobs opened up at the shipyard in order to produce these concrete ships, with 17% of those positions filled by women.[4] Geanie was one of the women who got a job as a welder. Welding trainees were paid 63 cents an hour, and the dangerous work led to regular injuries and lost limbs.[5]

On her accomplishments Geanie wrote, “My family thought I was liberated before anyone had even heard of ‘women’s liberation.’ I always knew men made more than women, so I applied for men’s jobs, knew what they made, asked for it, and got it. (Can’t hurt to ask, right?) Sometimes I even made more if I was able to get a percentage of a dump truck haul.” Additionally, she was proud that at the age of 85 when she wrote the memoir, that she was still active. “I keep house, cook, sew, make baby blankets, crochet afghans, make quilts, and note cards with fabric.”

[1] Shirley Herdge, interview by author, Brooksville, FL, September 15, 2019.

[2] Lewis N. Wynne, “Shipbuilding in Tampa During World War II,” Sunland Tribune 16 (1990),6.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Stacey Lynn Tanner, “Progress and Sacrifice: Tampa Shipyard Workers in World War II,” The Florida Historical Society Vol. 85, No. 4 (Spring 2007), 433.

[5] Ibid, 434-436.