U.S. Census Collection

Dublin Core

Title

U.S. Census Collection

Alternative Title

Census Collection

Subject

Census--United States

Population--United States

Orange County (Fla.)

Marion County (Fla.)

Brevard County (Fla.)

St. Lucie County (Fla.)

Seminole County (Fla.)

Volusia County (Fla.)

Flagler County (Fla.)

Lake County (Fla.)

Osceola County (Fla.)

Description

Collection of United States Census population records for various counties in Central Florida from 1840 to 2000.

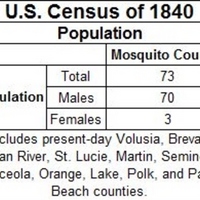

The Census Act of 1840 was signed into law on March 3, 1839 and later amended on February 26, 1840. This piece of legislation established a centralized census office during each enumeration. Congress designated the census questionnaire designs to the Secretary of State. However, each household received inquiries regarding "the pursuits, industry, education, and resources of the country" and included questions related to school attendance, literacy, and vocation.

In March of 1849, Congress pass legislation that established a census board consisting of the Secretary of State, the Attorney General, and the Postmaster General. The board was responsible for preparing and printing forms and schedules for enumeration related to population, mining, agriculture, commerce, manufacturing, education, etc. The 1850 Census also increased population inquiries to include every free person's name (as opposed to just the head of the household), as well as information on taxes, schools, crime, wages, estate values, etc.

The Census Act of 1850 authorized the U.S. Census of 1860 and stipulated that its provisions be adhered to for all future decennial censuses should no new legislation be passed by the first of the year of said census. In May of 1865, the U.S. Census Office was abolished and many superintending clerks were transferred to the General Land Office.

Although the 1870 Census was conducted under the provisions of the Census Act of 1850, a new act was passed on May 6, 1870. The new census legislation required two changes in procedures related to questionnaire return submission dates. Moreover, penalties for refusing to reply to inquires were expanded to apply to all questions and questionnaires. The questionnaires themselves had to be redesigned due to the end of the "slave questionnaire", as slavery had been formally abolished slavery nationwide via the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. This left five schedules for the census: General Population, Mortality, Agriculture, Products of Industry, and Social Statistics. In addition, the use of a Charles W. Seaton, a U.S. Census Office chief clerk and later superintendent, invited a rudimentary tallying machine that partially alleviated the difficulties of tallying and tabulating questionnaire responses. Finally, the new superintendent for the Ninth Census, General Francis A. Walker, introduced employment examinations to test the qualifications of applicants to the Census Office, allowing for increased efficiency in the process of collecting census data.

The newest act authorizing the Census of 1880 provided for supervision of enumeration by "supervisors of the census", selected exclusively for the collection of census data. All supervisors, as well as the superintendent, were to appointed by the U.S. President and approved by the Senate. Census enumerators were required to personally visit each household and family within his subdivision. The new census act also allowed for the collection of data related to the condition and operation of railroad corporations, incorporated express companies, and telegraph companies, as well as data related to the condition and operation of life, fire, and marine insurance companies. Corporations who refused to provide the census with "true and complete" answers were subject to fines. In addition, the census superintendent was required to collect and publish data on the population, industries and resources of the District of Alaska. Finally, the 1880 Census consisted of five schedules: Population, Mortality, Agriculture, Social Statistics, and Manufacturing.

The Census of 1890 was authorized by an act modeled after the 1880 enumeration and signed into law on March 1, 1889. The 1890 Census was supervised by 175 employees and enumerators were required to collect all information by personally visiting each household. The 1890 Census included essentially the same inquires from the 1880 Census, with some notable additions, such as questions about home and farm ownership and indebtedness; and the names, units, length of service, and residences of former Union soldiers and sailors, as well as the names of the widows of those who were no longer alive. Racial categorization was expanded to include "Japanese", along with "Chinese", "Negro", "mulatto", "quadroon", "octoroon", and "White". Herman Hollerith, a former employee of the U.S. Census Office, invited the electric tabulating system, which was widely used in the 1890 Census, allowing data to be processed faster and more efficiently. On October 3, 1893, Congress passed a law that transferred census-related work to the direction of the commissioner of labor. Congress passed another act on March 2, 1895, effectively abolishing the U.S. Census Office and transferring the remaining responsibilities to the Office of the Secretary of the Interior.

Congress limited the Census of 1900 to content related to population, mortality, agriculture, and manufacturing. Special census agents were authorized to collect statistics related to incidents of deafness, blindness, insanity, and juvenile delinquency; as well as data on religious bodies, utilities, mining, and transportation. The act authorizing the 1900 Census designated the enumeration of military personally to the U.S. Department of War and the U.S. Department of the Navy, while Indiana Territory was to be enumerated by the commissioner of Indian Affairs. Annexed in 1898, Hawaii was included in the census for the first time. In 1902, the U.S. Census Office was officially established as a permanent organization within the U.S. Department of the Interior. The office became the U.S. Census Bureau in 1903 and was transferred to the Department of Commerce and Labor.

The Census of 1910 was approved by legislation introduced in December of 1907 and enacted in July of 1909. The delay was the result of a disagreement over the appointment of enumerators. President Theodore Roosevelt supported the hiring of enumerators via the civil service system, while Congress supported enumerators as positions of patronage. President Roosevelt successfully won the debate. This census act also changed Census Day from the traditional date of June 1st to April 15th. Additional questions regarding the nationality and native language of foreign-born persons and their parents. Funds for the U.S. Census Bureau were also increased to expand the Census' permanent workforce and created several new full-time positions, including a geographer, a chief statistician, and an assistant director. The assistant director was to be appointed by the President and approved by the Senate, while all other census employees were hired on the basis of open, competitive examinations administered by the Civil Service Commission. Despite the use of automatic counting machinery, issues with the tabulation process persisted. Finally, with the United States' entrance into World War I in 1917, the U.S. Census Bureau became a source of even more valuable purpose: the Census was able to use population and economic data to report on the populations of draft-age men, as well as information regarding each state's industrial capabilities.

The Census of 1920 changed the date of Census Day from April 15th to January 1st, as requested by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which argued that farmers' memories and harvest information would be more accurate on this day. The U.S. Census Bureau was also authorized to hire additional employees at its headquarters in Washington, D.C. and to create a special field force to collect census data. The legislation authorizing the 1920 Census also allowed for a census of manufacturing to be conducted in 1921, and for such a census to be repeated every two years thereafter, as opposed to the traditional five-year census cycle. Furthermore, a census of agriculture and livestock was to be conducted in 1925 and to be repeated every ten years thereafter. In addition, penalties for those who refused to supply information or those who supplied false information were strengthened. As a result of these changes, census of population, manufacturing, and agriculture and livestock became increasingly independent of one another.

The "usual place of abode", the location where residents regularly slept, instead of where they worked or were visiting, became the new basis for enumeration in the 1920 Census. Those with no permanent or regular residence were listed as residents of the location that they were enumerated at. Enumeration related to institutional inmates and dependent, defective, and delinquent classes were also modified. Unlike the previous census, the 1920 Census did not have inquires related to unemployment, to Union or Confederate Army or Navy service, to the number of children born, or to the length of time that a couple had been married. The Census of 1920, however, did include four additional questions: one regarding year of naturalization and three regarding native languages. Issues also arose as a result of changes in international boundaries following World War I, particularly for persons declaring birth or parental birth in Austria-Hungary, Germany, Russia, or Turkey. In response, enumerators were required to ask said persons for their province, state, or region of birth. Enumerators were not required to ask individuals how to spell their names, nor were respondents required to provide proof of various pieces of information. Race was determined by the enumerator's impressions.

The act authorizing the 1930 Census was approved on June 18, 1929, allowing for a census of population, agriculture, irrigation, draining, distribution, unemployment, and mining. For the first time, specific questions for inquiry were left to the discretion of the Director of the Census. The Census encompassed each state, as well as the District of Columbia, Alaska, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico. The Governors of Guam, American Samoa, the Virginia Islands, and the Panama Canal Zone were responsible for conducting censuses in their territory. Between the date that the census act was passed and Census Day (April 1st), the stock market crashed, plunging the entire country into the Great Depression. In response, there were public and academic requests for access to unemployment data collected in the 1930 Census; however, the U.S. Census Bureau was unable to meet this demands and the bureau was accused of present unreliable data. Congress required a special unemployment census for January 1931, which ultimately confirmed the severity of the economic crisis. Another unemployment census was conducted in 1937, as mandated by Congress. Because this special census was voluntary, it allowed the Census Bureau to experiment with statistical sampling. Only two percent of households received a special census questionnaire.

Congress authorized the 1940 Census in August 1939, providing the Director of the Census the additional authority to conduct a national census of housing in each state, the District of Columbia, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, and Alaska. The housing census was conducted separately, though enumerators often collection housing information at the same time that they collected population information. The Census of 1940 was the first time that the U.S. Census Bureau used advanced statistical techniques. In particular, the census used probably sampling, which had only previously been tested in a trial census of unemployment conducted the Civil Works Administration during 1933-1934, in surveys of retail stores in the 1930s, and in an official sample survey of unemployment conducted amongst two percent of American households in 1937. Probability sampling allowed for the inclusion of additional demographic questions without increasing the burden on the collection process or on data processing. Moreover, sampling the U.S. Census Bureau was able to publish preliminary returns eight months before tabulations were completed. Likewise, the census increased its number of published tables, and also was able to complete data processing with higher quality and more efficiency. New census questions focused on employment, unemployment, internal migration, and incomes—reflecting on the concerns of the Great Depression, the country's housing stock, and the need for public housing programs.

The Census of 1950 encompassed every state, Alaska, Hawaii, American Samoa, the Panama Canal Zone, Guam, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, and other small American territories. For the first time, the U.S. Census Bureau enumerate American living abroad to account for members of the U.S. Armed Forces, vessel crew members, and government employees residing in foreign countries. The U.S. Department of Defense, the U.S. Department of State, the U.S. Maritime Administration, and several other federal agencies were responsible for distributing and collecting census questionnaires in a cooperative effort. Persons living abroad for reasons other than what is listed above had their census information reported by families or neighbors residing in the United States, but such data was criticized as unreliable and were not published in official statistics. The 1950 Census also included a new survey on residential financing collected separately on a sample basis from owners of owner-occupied properties, rental properties, and mortgage lenders. The accuracy of the new census was increased by improved enumerator training, the use of detailed street maps for enumerators, the publication of "Missed Person" forms in local newspapers, and the designation of a specific night to conduct a special enumeration of transient individuals. Moreover, a post-enumeration survey was conducted to further verify the accuracy of the original enumeration. A sample of approximately 3,500 small areas was compared to the original census data to identify households that may have been omitted initially. Likewise, a sample of approximately 22,000 households were re-interviewed to identify persons omitted in the original enumeration count. Though not used for the 1950 Census, the UNIVersal Automatic Computer I (UNIVAC I), the first non-military computer, was used to tabulate some of the statistics for the 1954 census of economy. In August of 1954, Congress codified various census statutes, such as the Fifteenth Census Act of 1929, authorizing the decennial census and other census.

The Census of 1960 was the first to be mailed to respondents. The U.S. Postal Service delivered census questionnaires to households, the head of household was required to complete the questionnaire, and an enumerator was to pick it up. The enumeration process was divided into two stages: first, select data for each person and dwelling unit was collected; and second, more detailed economic and social data was collected from a sample of households and dwelling units. The census questionnaires for the second stage were hand-delivered by enumerators as they were collecting data from the first stage. Households receiving the second census questionnaire were to complete the form and mail it to their local census office. Twenty-five percent of the population was giving additional sample questions. Because of the increased use of sampling, less populated areas were prone to sampling variation; however, this did not significantly decrease the usefulness of census statistics gathered. Moreover, increased use of sampling reduced data processing costs. Additional questions included in the 1960 Census were related to places of works and means of transportation to work. By 1960, nearly all census data was processed using computers. The U.S. Census Bureau used a Film Optical Sensing Device for Input to Computer (FOSDIC) for the first time, thus decreasing the amount of time and money required for data input.

In 1966, the U.S. Census Bureau sought suggestions from advisory committees and from the public, resulting in numerous proposals for additional inquiries related to the scope and structure of the census, as well as in public interest for the publication of additional census data. Researchers also concluded that the 1950 Census and the 1960 Census had undercounted certain segments of the population. Moreover, they noted a growing distrust of government activity and increased resistance to responding to the census. Simultaneously, both the public and private sectors expressed need for accurate information. The U.S. Census Bureau decreased its number of questions from 66 to 23 in an effort to simplify its products. A register for densely populated areas was also created to ensure that all housing units were accounted for. A Spanish-language questionnaire was also enclosed with census questionnaires in areas with a significant amount of Spanish-speaking households. Additionally, a question on Hispanic origins or descent was asked independently from race, but only on a five-percent sample. Only five questions were given to all individuals: relationship to household head, sex, race, age, and marital status. Additional questions were asked in smaller sample groups. This was also the first census in which respondents of urban areas were asked to mail their forms to the Census Bureau, rather than to hold questionnaires for enumerators.

Address Coding Guides were used to assign census geographic codes to questionnaires. Counts, a series of computer tape files, were an additional innovation used to increase the accuracy of census data. Count 1 consisted of complete count data for block groups and/or enumeration districts. Count 2 contained census tracts and minor civil/census county divisions, while Count 3 consisted of census blocks. Counts 4-6 provided sample census data for geographic areas of various population sizes. The Census Bureau also produced six Public Use Microdata Sample files, each of which contained complete information for a sample of approximately two million people. Finally, the Census Bureau developed the Summary Tape Processing Center Program, which was a group of organizations, both public and private, that processed census data from computer tapes.

For the 1990 Census, the U.S. Census Bureau utilized extensive user consultation prior to enumeration in order to refine both long and short form census questionnaires. The short form consisted of 13 questions and was given to the entire population. The long form asked 45 questions and was given to a 20 percent sample. The long form included topics related to marital history, carpooling, residence, residential elevators, and energy usage. Unlike the 1980 Census, the new census eliminated questions regarding air conditioning, the number of bathrooms in a residence, and the type of heating equipment used. A vast advertising campaign was marketed to increase public awareness of the census via public television, radio, and print media. Like the previous census, the Census of 1990 made a special effort to enumerate groups that have historically been undercounted in previous censuses called "S-Night": individuals in homeless shelters, soup kitchens, bus and railway stations, and dormitories (enumerated separately in the 1980 Census on "M-Night"); and permanent residents in hotels and motels (enumerated separately in the 1980 Census on "T-Night"). Following legal issues filed in response to the 1980 Census regarding statistical readjustment of undercounted areas, the Census Bureau initiated a post-enumeration survey (PES), in which a contemporaneous survey of households would be conducted and compare to the census results from the official census. In a partial resolution of a 1989 lawsuit filed by New York plaintiffs, the U.S. Department of Commerce agreed to use the PES to produce population data that had been adjusted for the projected undercount and that said data would be judged against the unadjusted data by the Secretary of Commerce's Special Advisory Panel (SAP).

The Census of 1990 also introduced the U.S. to the Topologically Integrated Geographic Encoding and Referencing System (TIGER), which was developed by the U.S. Geological Survey and the Census Bureau. TIGER used computerized representations of various map features to geographically code addresses into appropriate census geographic areas. It also produced different maps required for census data collection and tabulation. Five years earlier, the Census Bureau became the first government agency to publish information on CD-ROM. For the 1990 Census, the bureau made detailed census data, which had previously been only available to organizations with large mainframe computers, accessible to any individual with a personal computer. Census data was also available in print, on computer tape, and on microfiche. Using two online service vendors, DIALOG and CompuServe, the Census Bureau also published select census data online.

As with previous censuses, the 1990 Census undercounted the national population, and again, the African-American population had an estimated net undercount rate that was significantly higher than the rate for other races. In July of 1991, the Secretary of Commerce announced that he did not find evidence in favor of using adjusted counts compelling—despite SAP's split vote on the issue—and chose to use unadjusted totals for the official census results. In response, the New York plaintiffs resumed the lawsuit against the Department of Commerce. A federal district court divided in favor of the DOC in April of 1993. The U.S. Court of Appeals, however, rejected the previous court ruling and ordered that the case be reheard by the federal district court. In March of 1996, the U.S. Supreme Court finally ruled in favor of the Secretary of Commerce's decision to use the unadjusted census date, but did not rule on the legality or constitutionality of the use of statistical adjustment in producing apportionment counts.

For the 1990 Census, the U.S. Census Bureau utilized extensive user consultation prior to enumeration in order to refine both long and short form census questionnaires. The short form consisted of 13 questions and was given to the entire population. The long form asked 45 questions and was given to a 20 percent sample. The long form included topics related to marital history, carpooling, residence, residential elevators, and energy usage. Unlike the 1980 Census, the new census eliminated questions regarding air conditioning, the number of bathrooms in a residence, and the type of heating equipment used. A vast advertising campaign was marketed to increase public awareness of the census via public television, radio, and print media. Like the previous census, the Census of 1990 made a special effort to enumerate groups that have historically been undercounted in previous censuses called "S-Night": individuals in homeless shelters, soup kitchens, bus and railway stations, and dormitories (enumerated separately in the 1980 Census on "M-Night"); and permanent residents in hotels and motels (enumerated separately in the 1980 Census on "T-Night"). Following legal issues filed in response to the 1980 Census regarding statistical readjustment of undercounted areas, the Census Bureau initiated a post-enumeration survey (PES), in which a contemporaneous survey of households would be conducted and compare to the census results from the official census. In a partial resolution of a 1989 lawsuit filed by New York plaintiffs, the U.S. Department of Commerce agreed to use the PES to produce population data that had been adjusted for the projected undercount and that said data would be judged against the unadjusted data by the Secretary of Commerce's Special Advisory Panel (SAP).

The Census of 1990 also introduced the U.S. to the Topologically Integrated Geographic Encoding and Referencing System (TIGER), which was developed by the U.S. Geological Survey and the Census Bureau. TIGER used computerized representations of various map features to geographically code addresses into appropriate census geographic areas. It also produced different maps required for census data collection and tabulation. Five years earlier, the Census Bureau became the first government agency to publish information on CD-ROM. For the 1990 Census, the bureau made detailed census data, which had previously been only available to organizations with large mainframe computers, accessible to any individual with a personal computer. Census data was also available in print, on computer tape, and on microfiche. Using two online service vendors, DIALOG and CompuServe, the Census Bureau also published select census data online.

As with previous censuses, the 1990 Census undercounted the national population, and again, the African-American population had an estimated net undercount rate that was significantly higher than the rate for other races. In July of 1991, the Secretary of Commerce announced that he did not find evidence in favor of using adjusted counts compelling—despite SAP's split vote on the issue—and chose to use unadjusted totals for the official census results. In response, the New York plaintiffs resumed the lawsuit against the Department of Commerce. A federal district court divided in favor of the DOC in April of 1993. The U.S. Court of Appeals, however, rejected the previous court ruling and ordered that the case be reheard by the federal district court. In March of 1996, the U.S. Supreme Court finally ruled in favor of the Secretary of Commerce's decision to use the unadjusted census date, but did not rule on the legality or constitutionality of the use of statistical adjustment in producing apportionment counts.

For the Census of 2000, the short form consisted of only seven questions, while the long form consisted of 52 questions and used for a 17 percent sample of the population. For the first time, race questions were not limited to a single category; rather, respondents were able to check multiple boxes. A new question related to grandparents as caregivers was also mandated by legislation passed in 1996. Disability questions were expanded to including hearing and vision impairments, as well as learning, memory, and concentration disabilities. The 2000 Census also eliminated questions related to children born, water sources, sewage disposal, and condominium status. In addition, the 2000 Census was the first in which the Internet was used as the principal medium for the dissemination of census information. Summary Files were available for download immediately upon release and individual tables could be viewed via American FactFinder, the Census Bureau's online database. Files were also available for purchase on CD-Rom and DVD.

Due to declining questionnaire mail-back rates, the U.S. Census Bureau marketed a $167 million national and local print, television, and public advertising campaign in 17 different languages. The campaign successfully brought the mail-back rate up to 67 percent. Additionally, respondents receiving the short form were given the option of responding via the Internet. Telephone questionnaire assistance centers available in 6 languages also took responses via the phone. Statistical sampling techniques were utilized in two ways: first, to alter the traditional 100 percent personal visit of non-responding households during the non-response follow-up (NRFU) process by instead following up on a smaller sample basis; second, the sampling of 750,000 housing units matched to housing unit questionnaires obtained from mail and telephone responses, as well as from personal visits. The goal of the latter was to develop adjustment factors for individuals estimated to have been missed or duplicated and to correct the census counts to produce one set of numbers. This "one-number census" would correct for net coverage errors called Integrated Coverage Measurement (ICM). Both of these measures were taken in an attempt to avoid repetition of the litigation costs generated by the 1980 Census and the 1990 Census. Despite these efforts, two lawsuits—one filed by the U.S. House of Representatives—were filed in February 1998 challenging the constitutionality and legality of the planned uses of sampling to produce apportionment counts. Both cases were decided in favor of the plaintiffs in federal district courts, but the U.S. Department of Commerce made appeals to the U.S. Supreme Court. Known as the U.S. Department of Commerce v. the U.S. House of Representatives, the Court ruled that the Census Bureau's plans to use statistical sampling for purposes of congressional apportionments violated the Census Act. The bureau revised its plan, stating that it would produce statistically adjusted data for non-apportionment uses of census data information, such as redistricting. However, in March of 2001, the Census Bureau recommended against the use of adjusted census data for redistricting due to accuracy concerns; the Secretary of Commerce determined that the unadjusted data would be released as the bureau's official redistricting data. The Director of the Census Bureau also rejected to the use of adjusted data for non-redistricting purposes in October of that same year.

The Census Act of 1840 was signed into law on March 3, 1839 and later amended on February 26, 1840. This piece of legislation established a centralized census office during each enumeration. Congress designated the census questionnaire designs to the Secretary of State. However, each household received inquiries regarding "the pursuits, industry, education, and resources of the country" and included questions related to school attendance, literacy, and vocation.

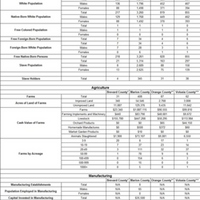

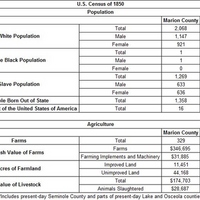

In March of 1849, Congress pass legislation that established a census board consisting of the Secretary of State, the Attorney General, and the Postmaster General. The board was responsible for preparing and printing forms and schedules for enumeration related to population, mining, agriculture, commerce, manufacturing, education, etc. The 1850 Census also increased population inquiries to include every free person's name (as opposed to just the head of the household), as well as information on taxes, schools, crime, wages, estate values, etc.

The Census Act of 1850 authorized the U.S. Census of 1860 and stipulated that its provisions be adhered to for all future decennial censuses should no new legislation be passed by the first of the year of said census. In May of 1865, the U.S. Census Office was abolished and many superintending clerks were transferred to the General Land Office.

Although the 1870 Census was conducted under the provisions of the Census Act of 1850, a new act was passed on May 6, 1870. The new census legislation required two changes in procedures related to questionnaire return submission dates. Moreover, penalties for refusing to reply to inquires were expanded to apply to all questions and questionnaires. The questionnaires themselves had to be redesigned due to the end of the "slave questionnaire", as slavery had been formally abolished slavery nationwide via the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. This left five schedules for the census: General Population, Mortality, Agriculture, Products of Industry, and Social Statistics. In addition, the use of a Charles W. Seaton, a U.S. Census Office chief clerk and later superintendent, invited a rudimentary tallying machine that partially alleviated the difficulties of tallying and tabulating questionnaire responses. Finally, the new superintendent for the Ninth Census, General Francis A. Walker, introduced employment examinations to test the qualifications of applicants to the Census Office, allowing for increased efficiency in the process of collecting census data.

The newest act authorizing the Census of 1880 provided for supervision of enumeration by "supervisors of the census", selected exclusively for the collection of census data. All supervisors, as well as the superintendent, were to appointed by the U.S. President and approved by the Senate. Census enumerators were required to personally visit each household and family within his subdivision. The new census act also allowed for the collection of data related to the condition and operation of railroad corporations, incorporated express companies, and telegraph companies, as well as data related to the condition and operation of life, fire, and marine insurance companies. Corporations who refused to provide the census with "true and complete" answers were subject to fines. In addition, the census superintendent was required to collect and publish data on the population, industries and resources of the District of Alaska. Finally, the 1880 Census consisted of five schedules: Population, Mortality, Agriculture, Social Statistics, and Manufacturing.

The Census of 1890 was authorized by an act modeled after the 1880 enumeration and signed into law on March 1, 1889. The 1890 Census was supervised by 175 employees and enumerators were required to collect all information by personally visiting each household. The 1890 Census included essentially the same inquires from the 1880 Census, with some notable additions, such as questions about home and farm ownership and indebtedness; and the names, units, length of service, and residences of former Union soldiers and sailors, as well as the names of the widows of those who were no longer alive. Racial categorization was expanded to include "Japanese", along with "Chinese", "Negro", "mulatto", "quadroon", "octoroon", and "White". Herman Hollerith, a former employee of the U.S. Census Office, invited the electric tabulating system, which was widely used in the 1890 Census, allowing data to be processed faster and more efficiently. On October 3, 1893, Congress passed a law that transferred census-related work to the direction of the commissioner of labor. Congress passed another act on March 2, 1895, effectively abolishing the U.S. Census Office and transferring the remaining responsibilities to the Office of the Secretary of the Interior.

Congress limited the Census of 1900 to content related to population, mortality, agriculture, and manufacturing. Special census agents were authorized to collect statistics related to incidents of deafness, blindness, insanity, and juvenile delinquency; as well as data on religious bodies, utilities, mining, and transportation. The act authorizing the 1900 Census designated the enumeration of military personally to the U.S. Department of War and the U.S. Department of the Navy, while Indiana Territory was to be enumerated by the commissioner of Indian Affairs. Annexed in 1898, Hawaii was included in the census for the first time. In 1902, the U.S. Census Office was officially established as a permanent organization within the U.S. Department of the Interior. The office became the U.S. Census Bureau in 1903 and was transferred to the Department of Commerce and Labor.

The Census of 1910 was approved by legislation introduced in December of 1907 and enacted in July of 1909. The delay was the result of a disagreement over the appointment of enumerators. President Theodore Roosevelt supported the hiring of enumerators via the civil service system, while Congress supported enumerators as positions of patronage. President Roosevelt successfully won the debate. This census act also changed Census Day from the traditional date of June 1st to April 15th. Additional questions regarding the nationality and native language of foreign-born persons and their parents. Funds for the U.S. Census Bureau were also increased to expand the Census' permanent workforce and created several new full-time positions, including a geographer, a chief statistician, and an assistant director. The assistant director was to be appointed by the President and approved by the Senate, while all other census employees were hired on the basis of open, competitive examinations administered by the Civil Service Commission. Despite the use of automatic counting machinery, issues with the tabulation process persisted. Finally, with the United States' entrance into World War I in 1917, the U.S. Census Bureau became a source of even more valuable purpose: the Census was able to use population and economic data to report on the populations of draft-age men, as well as information regarding each state's industrial capabilities.

The Census of 1920 changed the date of Census Day from April 15th to January 1st, as requested by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which argued that farmers' memories and harvest information would be more accurate on this day. The U.S. Census Bureau was also authorized to hire additional employees at its headquarters in Washington, D.C. and to create a special field force to collect census data. The legislation authorizing the 1920 Census also allowed for a census of manufacturing to be conducted in 1921, and for such a census to be repeated every two years thereafter, as opposed to the traditional five-year census cycle. Furthermore, a census of agriculture and livestock was to be conducted in 1925 and to be repeated every ten years thereafter. In addition, penalties for those who refused to supply information or those who supplied false information were strengthened. As a result of these changes, census of population, manufacturing, and agriculture and livestock became increasingly independent of one another.

The "usual place of abode", the location where residents regularly slept, instead of where they worked or were visiting, became the new basis for enumeration in the 1920 Census. Those with no permanent or regular residence were listed as residents of the location that they were enumerated at. Enumeration related to institutional inmates and dependent, defective, and delinquent classes were also modified. Unlike the previous census, the 1920 Census did not have inquires related to unemployment, to Union or Confederate Army or Navy service, to the number of children born, or to the length of time that a couple had been married. The Census of 1920, however, did include four additional questions: one regarding year of naturalization and three regarding native languages. Issues also arose as a result of changes in international boundaries following World War I, particularly for persons declaring birth or parental birth in Austria-Hungary, Germany, Russia, or Turkey. In response, enumerators were required to ask said persons for their province, state, or region of birth. Enumerators were not required to ask individuals how to spell their names, nor were respondents required to provide proof of various pieces of information. Race was determined by the enumerator's impressions.

The act authorizing the 1930 Census was approved on June 18, 1929, allowing for a census of population, agriculture, irrigation, draining, distribution, unemployment, and mining. For the first time, specific questions for inquiry were left to the discretion of the Director of the Census. The Census encompassed each state, as well as the District of Columbia, Alaska, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico. The Governors of Guam, American Samoa, the Virginia Islands, and the Panama Canal Zone were responsible for conducting censuses in their territory. Between the date that the census act was passed and Census Day (April 1st), the stock market crashed, plunging the entire country into the Great Depression. In response, there were public and academic requests for access to unemployment data collected in the 1930 Census; however, the U.S. Census Bureau was unable to meet this demands and the bureau was accused of present unreliable data. Congress required a special unemployment census for January 1931, which ultimately confirmed the severity of the economic crisis. Another unemployment census was conducted in 1937, as mandated by Congress. Because this special census was voluntary, it allowed the Census Bureau to experiment with statistical sampling. Only two percent of households received a special census questionnaire.

Congress authorized the 1940 Census in August 1939, providing the Director of the Census the additional authority to conduct a national census of housing in each state, the District of Columbia, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, and Alaska. The housing census was conducted separately, though enumerators often collection housing information at the same time that they collected population information. The Census of 1940 was the first time that the U.S. Census Bureau used advanced statistical techniques. In particular, the census used probably sampling, which had only previously been tested in a trial census of unemployment conducted the Civil Works Administration during 1933-1934, in surveys of retail stores in the 1930s, and in an official sample survey of unemployment conducted amongst two percent of American households in 1937. Probability sampling allowed for the inclusion of additional demographic questions without increasing the burden on the collection process or on data processing. Moreover, sampling the U.S. Census Bureau was able to publish preliminary returns eight months before tabulations were completed. Likewise, the census increased its number of published tables, and also was able to complete data processing with higher quality and more efficiency. New census questions focused on employment, unemployment, internal migration, and incomes—reflecting on the concerns of the Great Depression, the country's housing stock, and the need for public housing programs.

The Census of 1950 encompassed every state, Alaska, Hawaii, American Samoa, the Panama Canal Zone, Guam, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, and other small American territories. For the first time, the U.S. Census Bureau enumerate American living abroad to account for members of the U.S. Armed Forces, vessel crew members, and government employees residing in foreign countries. The U.S. Department of Defense, the U.S. Department of State, the U.S. Maritime Administration, and several other federal agencies were responsible for distributing and collecting census questionnaires in a cooperative effort. Persons living abroad for reasons other than what is listed above had their census information reported by families or neighbors residing in the United States, but such data was criticized as unreliable and were not published in official statistics. The 1950 Census also included a new survey on residential financing collected separately on a sample basis from owners of owner-occupied properties, rental properties, and mortgage lenders. The accuracy of the new census was increased by improved enumerator training, the use of detailed street maps for enumerators, the publication of "Missed Person" forms in local newspapers, and the designation of a specific night to conduct a special enumeration of transient individuals. Moreover, a post-enumeration survey was conducted to further verify the accuracy of the original enumeration. A sample of approximately 3,500 small areas was compared to the original census data to identify households that may have been omitted initially. Likewise, a sample of approximately 22,000 households were re-interviewed to identify persons omitted in the original enumeration count. Though not used for the 1950 Census, the UNIVersal Automatic Computer I (UNIVAC I), the first non-military computer, was used to tabulate some of the statistics for the 1954 census of economy. In August of 1954, Congress codified various census statutes, such as the Fifteenth Census Act of 1929, authorizing the decennial census and other census.

The Census of 1960 was the first to be mailed to respondents. The U.S. Postal Service delivered census questionnaires to households, the head of household was required to complete the questionnaire, and an enumerator was to pick it up. The enumeration process was divided into two stages: first, select data for each person and dwelling unit was collected; and second, more detailed economic and social data was collected from a sample of households and dwelling units. The census questionnaires for the second stage were hand-delivered by enumerators as they were collecting data from the first stage. Households receiving the second census questionnaire were to complete the form and mail it to their local census office. Twenty-five percent of the population was giving additional sample questions. Because of the increased use of sampling, less populated areas were prone to sampling variation; however, this did not significantly decrease the usefulness of census statistics gathered. Moreover, increased use of sampling reduced data processing costs. Additional questions included in the 1960 Census were related to places of works and means of transportation to work. By 1960, nearly all census data was processed using computers. The U.S. Census Bureau used a Film Optical Sensing Device for Input to Computer (FOSDIC) for the first time, thus decreasing the amount of time and money required for data input.

In 1966, the U.S. Census Bureau sought suggestions from advisory committees and from the public, resulting in numerous proposals for additional inquiries related to the scope and structure of the census, as well as in public interest for the publication of additional census data. Researchers also concluded that the 1950 Census and the 1960 Census had undercounted certain segments of the population. Moreover, they noted a growing distrust of government activity and increased resistance to responding to the census. Simultaneously, both the public and private sectors expressed need for accurate information. The U.S. Census Bureau decreased its number of questions from 66 to 23 in an effort to simplify its products. A register for densely populated areas was also created to ensure that all housing units were accounted for. A Spanish-language questionnaire was also enclosed with census questionnaires in areas with a significant amount of Spanish-speaking households. Additionally, a question on Hispanic origins or descent was asked independently from race, but only on a five-percent sample. Only five questions were given to all individuals: relationship to household head, sex, race, age, and marital status. Additional questions were asked in smaller sample groups. This was also the first census in which respondents of urban areas were asked to mail their forms to the Census Bureau, rather than to hold questionnaires for enumerators.

Address Coding Guides were used to assign census geographic codes to questionnaires. Counts, a series of computer tape files, were an additional innovation used to increase the accuracy of census data. Count 1 consisted of complete count data for block groups and/or enumeration districts. Count 2 contained census tracts and minor civil/census county divisions, while Count 3 consisted of census blocks. Counts 4-6 provided sample census data for geographic areas of various population sizes. The Census Bureau also produced six Public Use Microdata Sample files, each of which contained complete information for a sample of approximately two million people. Finally, the Census Bureau developed the Summary Tape Processing Center Program, which was a group of organizations, both public and private, that processed census data from computer tapes.

For the 1990 Census, the U.S. Census Bureau utilized extensive user consultation prior to enumeration in order to refine both long and short form census questionnaires. The short form consisted of 13 questions and was given to the entire population. The long form asked 45 questions and was given to a 20 percent sample. The long form included topics related to marital history, carpooling, residence, residential elevators, and energy usage. Unlike the 1980 Census, the new census eliminated questions regarding air conditioning, the number of bathrooms in a residence, and the type of heating equipment used. A vast advertising campaign was marketed to increase public awareness of the census via public television, radio, and print media. Like the previous census, the Census of 1990 made a special effort to enumerate groups that have historically been undercounted in previous censuses called "S-Night": individuals in homeless shelters, soup kitchens, bus and railway stations, and dormitories (enumerated separately in the 1980 Census on "M-Night"); and permanent residents in hotels and motels (enumerated separately in the 1980 Census on "T-Night"). Following legal issues filed in response to the 1980 Census regarding statistical readjustment of undercounted areas, the Census Bureau initiated a post-enumeration survey (PES), in which a contemporaneous survey of households would be conducted and compare to the census results from the official census. In a partial resolution of a 1989 lawsuit filed by New York plaintiffs, the U.S. Department of Commerce agreed to use the PES to produce population data that had been adjusted for the projected undercount and that said data would be judged against the unadjusted data by the Secretary of Commerce's Special Advisory Panel (SAP).

The Census of 1990 also introduced the U.S. to the Topologically Integrated Geographic Encoding and Referencing System (TIGER), which was developed by the U.S. Geological Survey and the Census Bureau. TIGER used computerized representations of various map features to geographically code addresses into appropriate census geographic areas. It also produced different maps required for census data collection and tabulation. Five years earlier, the Census Bureau became the first government agency to publish information on CD-ROM. For the 1990 Census, the bureau made detailed census data, which had previously been only available to organizations with large mainframe computers, accessible to any individual with a personal computer. Census data was also available in print, on computer tape, and on microfiche. Using two online service vendors, DIALOG and CompuServe, the Census Bureau also published select census data online.

As with previous censuses, the 1990 Census undercounted the national population, and again, the African-American population had an estimated net undercount rate that was significantly higher than the rate for other races. In July of 1991, the Secretary of Commerce announced that he did not find evidence in favor of using adjusted counts compelling—despite SAP's split vote on the issue—and chose to use unadjusted totals for the official census results. In response, the New York plaintiffs resumed the lawsuit against the Department of Commerce. A federal district court divided in favor of the DOC in April of 1993. The U.S. Court of Appeals, however, rejected the previous court ruling and ordered that the case be reheard by the federal district court. In March of 1996, the U.S. Supreme Court finally ruled in favor of the Secretary of Commerce's decision to use the unadjusted census date, but did not rule on the legality or constitutionality of the use of statistical adjustment in producing apportionment counts.

For the 1990 Census, the U.S. Census Bureau utilized extensive user consultation prior to enumeration in order to refine both long and short form census questionnaires. The short form consisted of 13 questions and was given to the entire population. The long form asked 45 questions and was given to a 20 percent sample. The long form included topics related to marital history, carpooling, residence, residential elevators, and energy usage. Unlike the 1980 Census, the new census eliminated questions regarding air conditioning, the number of bathrooms in a residence, and the type of heating equipment used. A vast advertising campaign was marketed to increase public awareness of the census via public television, radio, and print media. Like the previous census, the Census of 1990 made a special effort to enumerate groups that have historically been undercounted in previous censuses called "S-Night": individuals in homeless shelters, soup kitchens, bus and railway stations, and dormitories (enumerated separately in the 1980 Census on "M-Night"); and permanent residents in hotels and motels (enumerated separately in the 1980 Census on "T-Night"). Following legal issues filed in response to the 1980 Census regarding statistical readjustment of undercounted areas, the Census Bureau initiated a post-enumeration survey (PES), in which a contemporaneous survey of households would be conducted and compare to the census results from the official census. In a partial resolution of a 1989 lawsuit filed by New York plaintiffs, the U.S. Department of Commerce agreed to use the PES to produce population data that had been adjusted for the projected undercount and that said data would be judged against the unadjusted data by the Secretary of Commerce's Special Advisory Panel (SAP).

The Census of 1990 also introduced the U.S. to the Topologically Integrated Geographic Encoding and Referencing System (TIGER), which was developed by the U.S. Geological Survey and the Census Bureau. TIGER used computerized representations of various map features to geographically code addresses into appropriate census geographic areas. It also produced different maps required for census data collection and tabulation. Five years earlier, the Census Bureau became the first government agency to publish information on CD-ROM. For the 1990 Census, the bureau made detailed census data, which had previously been only available to organizations with large mainframe computers, accessible to any individual with a personal computer. Census data was also available in print, on computer tape, and on microfiche. Using two online service vendors, DIALOG and CompuServe, the Census Bureau also published select census data online.

As with previous censuses, the 1990 Census undercounted the national population, and again, the African-American population had an estimated net undercount rate that was significantly higher than the rate for other races. In July of 1991, the Secretary of Commerce announced that he did not find evidence in favor of using adjusted counts compelling—despite SAP's split vote on the issue—and chose to use unadjusted totals for the official census results. In response, the New York plaintiffs resumed the lawsuit against the Department of Commerce. A federal district court divided in favor of the DOC in April of 1993. The U.S. Court of Appeals, however, rejected the previous court ruling and ordered that the case be reheard by the federal district court. In March of 1996, the U.S. Supreme Court finally ruled in favor of the Secretary of Commerce's decision to use the unadjusted census date, but did not rule on the legality or constitutionality of the use of statistical adjustment in producing apportionment counts.

For the Census of 2000, the short form consisted of only seven questions, while the long form consisted of 52 questions and used for a 17 percent sample of the population. For the first time, race questions were not limited to a single category; rather, respondents were able to check multiple boxes. A new question related to grandparents as caregivers was also mandated by legislation passed in 1996. Disability questions were expanded to including hearing and vision impairments, as well as learning, memory, and concentration disabilities. The 2000 Census also eliminated questions related to children born, water sources, sewage disposal, and condominium status. In addition, the 2000 Census was the first in which the Internet was used as the principal medium for the dissemination of census information. Summary Files were available for download immediately upon release and individual tables could be viewed via American FactFinder, the Census Bureau's online database. Files were also available for purchase on CD-Rom and DVD.

Due to declining questionnaire mail-back rates, the U.S. Census Bureau marketed a $167 million national and local print, television, and public advertising campaign in 17 different languages. The campaign successfully brought the mail-back rate up to 67 percent. Additionally, respondents receiving the short form were given the option of responding via the Internet. Telephone questionnaire assistance centers available in 6 languages also took responses via the phone. Statistical sampling techniques were utilized in two ways: first, to alter the traditional 100 percent personal visit of non-responding households during the non-response follow-up (NRFU) process by instead following up on a smaller sample basis; second, the sampling of 750,000 housing units matched to housing unit questionnaires obtained from mail and telephone responses, as well as from personal visits. The goal of the latter was to develop adjustment factors for individuals estimated to have been missed or duplicated and to correct the census counts to produce one set of numbers. This "one-number census" would correct for net coverage errors called Integrated Coverage Measurement (ICM). Both of these measures were taken in an attempt to avoid repetition of the litigation costs generated by the 1980 Census and the 1990 Census. Despite these efforts, two lawsuits—one filed by the U.S. House of Representatives—were filed in February 1998 challenging the constitutionality and legality of the planned uses of sampling to produce apportionment counts. Both cases were decided in favor of the plaintiffs in federal district courts, but the U.S. Department of Commerce made appeals to the U.S. Supreme Court. Known as the U.S. Department of Commerce v. the U.S. House of Representatives, the Court ruled that the Census Bureau's plans to use statistical sampling for purposes of congressional apportionments violated the Census Act. The bureau revised its plan, stating that it would produce statistically adjusted data for non-apportionment uses of census data information, such as redistricting. However, in March of 2001, the Census Bureau recommended against the use of adjusted census data for redistricting due to accuracy concerns; the Secretary of Commerce determined that the unadjusted data would be released as the bureau's official redistricting data. The Director of the Census Bureau also rejected to the use of adjusted data for non-redistricting purposes in October of that same year.

Contributor

Gibson, Ella

Is Part Of

Language

eng

Type

Collection

Coverage

Mosquito County, Florida

Brevard County, Florida

Flagler County, Florida

Lake County, Florida

Marion County, Florida

Orange County, Florida

Osceola County, Florida

Seminole County, Florida

Volusia County, Florida

Rights Holder

This resource is not subject to copyright in the United States and there are no copyright restrictions on reproduction, derivative works, distribution, performance, or display of the work. Anyone may, without restriction under U.S. copyright laws:

- reproduce the work in print or digital form

- create derivative works

- perform the work publicly

- display the work

- distribute copies or digitally transfer the work to the public by sale or other transfer of ownership, or by rental, lease, or lending.

Curator

Cepero, Laura

Digital Collection

Source Repository

External Reference

United States. Historical Statistics of the United States: Colonial Times to 1970. Washington: U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, 1975. https://www.census.gov/history/pdf/histstats-colonial-1970.pdf.

United States, and Carroll D. Wright. The History and Growth of the United States Census. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1900. https://www.census.gov/history/pdf/wright-hunt.pdf.

"Through the Decades." United States Census Bureau, United States Department of Commerce. https://www.census.gov/history/www/through_the_decades/.

Collection Items

U.S. Census for Central Florida, 2000

The Twenty-Second United States Census records for Brevard County, Flagler County, Lake County, Marion County, Orange County, Osceola County, Seminole County, and Volusia County, Florida, for 2000. The census divides the population by gender, race…

U.S. Census for Central Florida, 1990

The Twenty-First United States Census records for Brevard County, Flagler County, Lake County, Marion County, Orange County, Osceola County, Seminole County, and Volusia County, Florida, for 1990. The census divides the population by gender, race…

U.S. Census for Central Florida, 1980

The Twentieth United States Census records for Brevard County, Flagler County, Lake County, Marion County, Orange County, Osceola County, Seminole County, and Volusia County, Florida for 1980. The census divides the population by gender, race…

U.S. Census for Central Florida, 1970

The Nineteenth United States Census records for Brevard County, Flagler County, Lake County, Marion County, Orange County, Osceola County, Seminole County, and Volusia County, Florida, for 1970. The census divides the population by gender, race…

U.S. Census for Central Florida, 1960

The Eighteenth United States Census records for Brevard County, Flagler County, Lake County, Marion County, Orange County, Osceola County, Seminole County, and Volusia County, Florida, for 1960. The census divides the population by gender, race…

U.S. Census for Central Florida, 1950

The Seventeenth United States Census records for Brevard County, Flagler County, Lake County, Marion County, Orange County, Osceola County, Seminole County, and Volusia County, Florida, for 1950. The census divides the population by gender, race…

U.S. Census for Central Florida, 1940

The Sixteenth United States Census records for Brevard County, Flagler County, Lake County, Marion County, Orange County, Osceola County, Seminole County, and Volusia County, Florida for 1940. The census divides the population by gender, race…

U.S. Census for Central Florida, 1930

The Fifteenth United States Census records for Brevard County, Flagler County, Lake County, Marion County, Orange County, Osceola County, Seminole County, and Volusia County, Florida, for 1930. The census divides the population by gender, race…

U.S. Census for Central Florida, 1920

The Fourteenth United States Census records for Brevard County, Flagler County, Lake County, Marion County, Orange County, Osceola County, Seminole County, and Volusia County, Florida for 1920. The census divides the population by gender, race…

U.S. Census for Central Florida, 1910

The Thirteenth United States Census records for Brevard County, Lake County, Marion County, Orange County (including present-day Seminole County), Osceola County, and Volusia County (including present-day Flagler County), Florida, for 1910. The…

U.S. Census for Central Florida, 1900

The Twelfth United States Census records for Brevard County, Lake County, Marion County, Orange County (including present-day Seminole County), Osceola County, and Volusia County (including present-day Flagler County), Florida, for 1900. The census…

U.S. Census for Central Florida, 1890

The Eleventh United States Census records for Brevard County, Lake County, Marion County, Orange County (including present-day Seminole County), Osceola County, and Volusia County (including present-day Flagler County), Florida, for 1890. The census…

U.S. Census for Central Florida, 1880

The Tenth United States Census records for Brevard County (including present-day St. Lucie County), Marion County, Orange County (including present-day Seminole County and parts of present-day Lake County, Osceola County, and Volusia County), and…

U.S. Census for Central Florida, 1870

The Ninth United States Census records for Brevard County (including present-day St. Lucie County), Marion County, Orange County (including present-day Seminole County and parts of present-day Lake and Osceola counties), and Volusia County (including…

U.S. Census for Central Florida, 1860

The Eighth United States Census records for Brevard County (including present-day St. Lucie County), Marion County, Orange County (including present-day Seminole County and parts of present-day Lake and Osceola counties), and Volusia County…

U.S. Census for Central Florida, 1850

The Seventh United States Census records for Orange County (including present-day Seminole County and part of Lake County and Osceola County) and Marion County for 1850. The census divides the population by race ("White" vs. "Black") and gender. The…

U.S. Census for Central Florida, 1840

The Sixth United States Census population records for Mosquito County (including present-day Volusia, Brevard, Indian River, St. Lucie, Martin, Seminole, Osceola, Orange, Lake, Polk, and Palm Beach counties) for 1840.The Census Act of 1840 was signed…

Collection Tree

- U.S. Census Collection